Payroll & Finance

Demystifying the Holidays Act

May 19, 2019

As all New Zealand employers know, the Holidays Act 2003 is a very challenging piece of legislation.

Over the past few years, many organisations have been found not to have complied with the Act, mostly because of mistakes calculating holiday pay.

In 2016, the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) estimated the number of workers that have been underpaid could be more than 700,000, at a total cost of over $2 billion.

The fact that MBIE is one of the organisations that has had problems correctly working out employees’ holiday pay shows how tricky complying with the Holidays Act can be (other high-profile employers include the police, the Corrections Department, Ministry of Justice, some District Health Boards, and Bunnings).

In my experience, most non-compliance isn’t because businesses want to shortchange their workers; it’s a result of people not being able to figure out what should and should not be paid.

Thankfully, the government has recognised the difficulties employers have in following the Holidays Act and currently has a taskforce looking at ways to make it more straightforward. However, we’re going to have to wait until the middle of this year for the working group to report back and even if it recommends any changes, they could take some time to come into effect.

In the meantime, understanding the Act and how to correctly calculate holiday and leave pay is essential. All employers are legally obliged to ensure their employees get the holiday and leave entitlements and payments that are set out in the Act.

So, let’s cover the basics.

Annual leave

All permanent and some fixed-term employees are entitled to at least four weeks’ paid annual holidays (annual leave) for every 12 months of continuous employment, or part thereof.

Some employees – such as those on fixed-term agreements of less than 12 months or genuine casuals – may get paid for holidays on a pay-as-you-go basis at a rate of at least 8% of their gross earnings.

For permanent and some fixed-term employees, payment for annual leave is based on the greater of either:

ordinary weekly pay (what the employee receives under their employment agreement for an ordinary working week or the average of the last four weeks); or

average weekly earnings (the average of an employee’s earnings in the last 52 weeks prior to the current pay cycle or if they haven’t worked 52 weeks, the average pay for the number of weeks worked).

This is calculated at the time the employee takes annual leave.

It is critical to understand what an employee’s ordinary week consists of. For example, for a person who regularly works Monday to Friday, eight hours a day, a week is 40 hours. For a person who only works 14 hours on a Monday, their week is just 14 hours.

Watch out for

Calculating leave in hours or days – many payroll systems calculate leave in terms of hours (or days), rather than weeks, but the law requires that employees receive an entitlement of 4 weeks leave each year. To ensure that employees receive their correct entitlement, leave balances may need to be updated whenever the employee’s work pattern of hours or days per week changes.

Variable work patterns – if a worker does overtime or picks up extra shifts throughout the year, these need to be included in working week and pay calculations.

Commissions, allowances, or bonus payments – any payment that attracts PAYE tax needs to be included in calculations, as it is considered earnings. Note: reimbursements and discretionary payments are exempt, but any form of regular payment is not viewed as discretionary. (Be very careful about the term “discretionary”, as many employers get caught out. Just because an employment agreement says the bonus is discretionary, it doesn’t necessarily mean it is considered discretionary for the purposes of calculating leave.)

Find out more about what payments to include on the Employment.govt.nz website

Lump sum holiday payments – the Holidays Act requires that annual leave is paid in a lump sum before the start of leave. This can cause cash-flow problems for the business and can be administratively cumbersome, requiring an extra pay-run (it might also be unpopular with employees). Paying annual leave during the holiday, on the normal company pay-cycle, is much easier. To do this, you simply need a clause in the employment agreement stating leave will be paid as per the employee’s normal pay cycle.

Public holidays

All employees are entitled to payment on a public holiday if the holiday falls on a day they’d normally work (known as an ‘otherwise working day’).

Payment for a public holiday is relevant daily pay, i.e. the rate the employee would ordinarily be paid on the day leave is taken. If this can’t be worked out, you can use average daily pay.

If an employee works on a public holiday, they are entitled to payment for the hours they work, paid at time-and-a-half, and a day in lieu (an alternative day). An alternative day is only given if the public holiday is an otherwise working day.

Unused alternative days can be exchanged for payment after 12 months, but not before.

Watch out for

Working a part day – if an employee only works a part day on a public holiday, they must be paid for the hours they worked (at time-and-a-half) but are entitled to a full alternative day, if the day was an otherwise working day.

Working on a public holiday that’s not an otherwise working day – in this case, an employee is entitled to pay at time-and-a-half, but not an alternative day.

Sick leave

After six months of current continuous employment, employees are entitled to five days’ paid sick leave a year.

Casual employees (those who haven’t been employed continuously for six months) are entitled to five days’ sick leave if they have worked for the business for six months for:

an average of at least 10 hours per week; and

at least one hour per week or 40 hours a month.

Unused sick leave can accrue up to a maximum of 20 days.

Payment for sick leave is relevant daily pay, or if this can’t be worked out, you can use average daily pay.

Watch out for

Part time or casual workers – five days’ sick leave is not pro rata, so employees are entitled to it regardless of the length of their working week.

Variable work patterns – if an employee hours of work aren’t the same each day, you must pay them for the numbers of hours they would have worked on the day they take sick leave. Averaging out the weekly hours could mean you underpay or overpay your workers for sick leave.

Part days – the Act only describes sick leave in terms of full days. However, you and your employee can agree to pro-rata deductions, such as part-days, half-days, or hours.

Bereavement leave

Like sick leave, all employees are entitled to bereavement leave after six months of current continuous employment.

However, if employment has not been continuous for six months, employees still get bereavement leave if they have worked for the business for six months for:

an average of at least 10 hours per week; and

at least one hour per week or 40 hours a month.

If the bereavement is of an immediate family member (spouse/partner, parent, child, sibling, grandparent, grandchild, or their spouse’s or partner’s parent), employees are entitled to up to three days’ leave. If the bereavement is outside the employee’s immediate family, they are entitled to one day’s leave.

Payment for bereavement leave is relevant daily pay or if this can’t be worked out, average daily pay.

Calculating relevant daily pay

Relevant daily pay is the amount the employee would have earned if they were at work on the day. This includes:

payments such as regular (taxable) allowances, commission, and bonuses;

overtime payments;

the cash value of board or lodgings (if this has been provided by the employer).

Average daily pay

In cases where it’s not possible or practicable to work out relevant daily pay or an employee’s daily pay varies in the pay period in question, you can use average daily pay.

Average daily pay is the daily average of the employers gross earnings over the past 52 weeks divided by the number of days or part days they worked, including time off on paid leave.

Final words to the wise

Follow the law. Even if everyone in the business agrees to a provision that doesn’t comply with the Holidays Act, it is still a breach and could be ruled so by the Labour Inspectorate or MBIE.

This legislation is extremely complex, but that is not an excuse for not getting things right. Take the time to calculate leave and payments carefully, each time you make them. Engaging with your employees in good faith will also help with compliance, especially when leave entitlements are hard to calculate.

Check the inputs into your payroll system are correct. This should mean the outputs comply with the law.

If there’s any doubt, err on the side of caution. Any breach could result in your business being liable for significant back payments and other penalties. Errors might only be tiny individually, but they could add up to a really large sum.

If you need help or advice, professional help is out there.

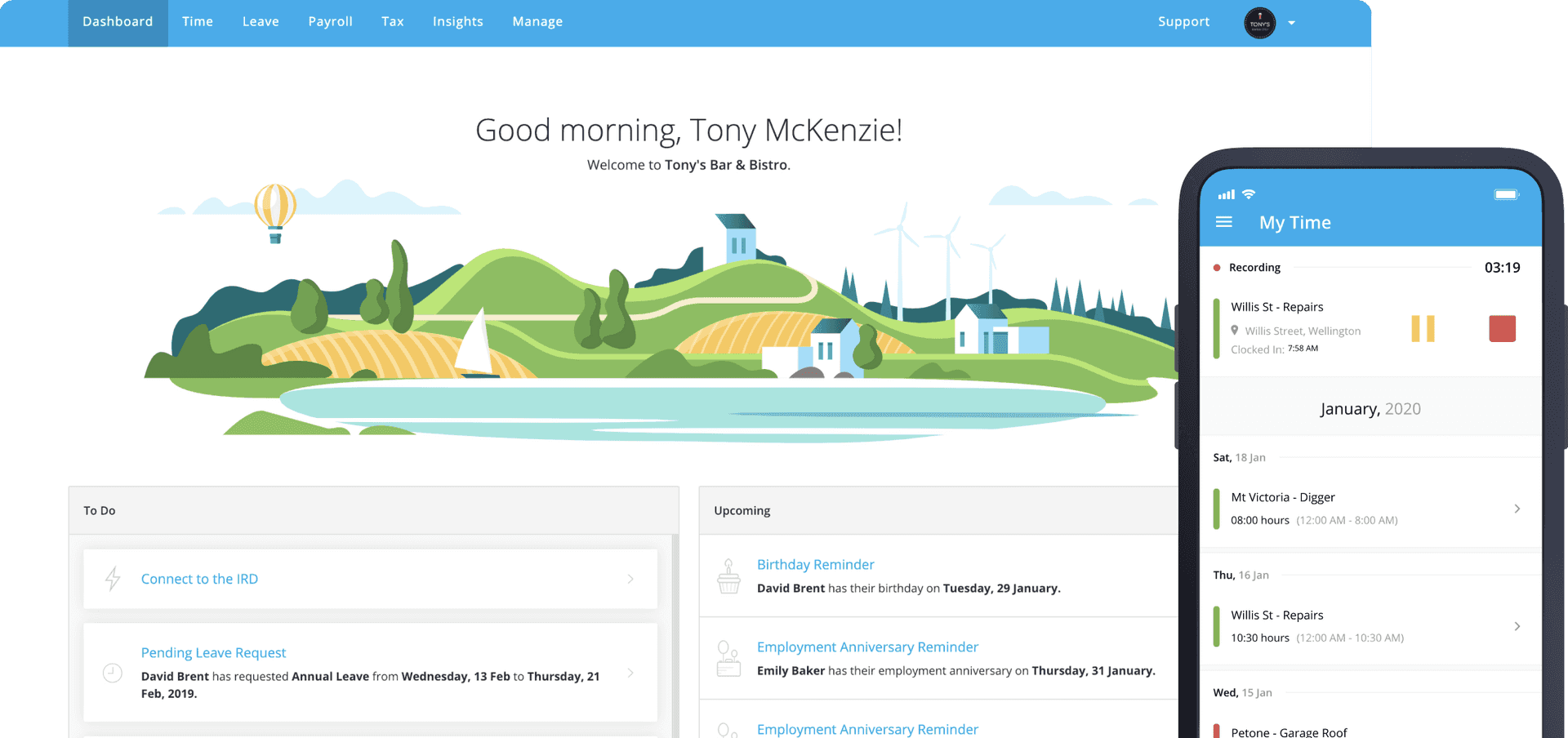

About MyHR

Jason launched MyHR in 2013 with a vision to change the face of HR. MyHR is intuitive, easy-to-use, online HR software, coupled with a team of dedicated HR professionals, providing customised support to over 600 organisations who employ 10,000 people in NZ, Australia, UK and Singapore.